Last week we lost one of the greatest statisticians of our time. A clinician who informed scholars and audiences world over; and a researcher whose work on economic development and global health changed the way we view our world. Personally, too, I have lost a role model, Dr Hans Rosling of the Karolinska Institute.

Nonetheless, Dr Rosling’s memory, influence and legacy remain with us.

He inspired me; and my serendipitous exposure to his work played a major part in making me who I am today. Not only did Dr Rosling’s work in the fields of public health and economic development inform audiences world over, but his dedication and contribution to informing professionals, pharmaceutical companies, public health workers and laypeople across the globe will not soon be forgotten.

So, in tribute, this article will memorialize the seven major lessons I learned from listening to and reading the work of Professor Hans Rosling.

-

“We live in a one hump world”

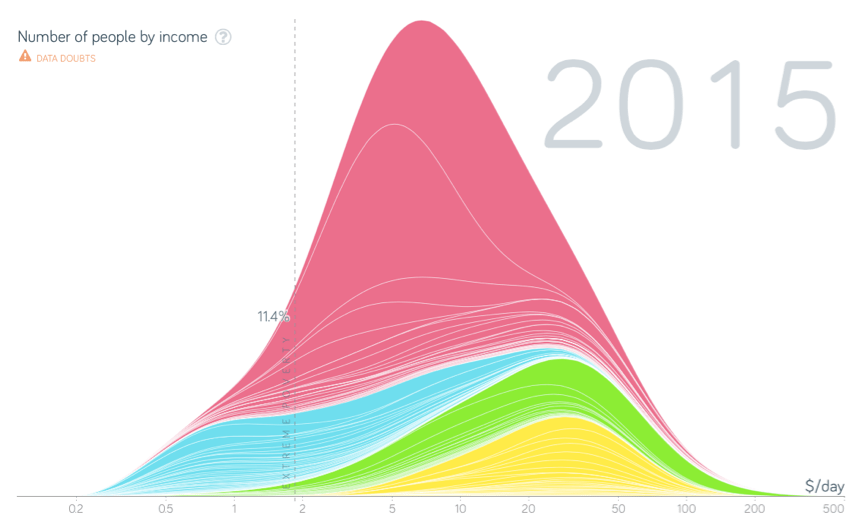

Figure 1: Asian countries, including Australasia are shown in pink; African nations in blue; Americas in green and European nations including Turkey, in yellow. The y-axis represents population.

The long-term readers amongst you will know that I am a proud South African. A member of the BRICS – the large, emerging, middle income powers of the world. The “nearly theres but not quite”, to some.

Using data and the excellent visuals generated by his Gapminder foundation’s revolutionary software; Dr Rosling demonstrated to us how so many of our traditional views on wealth and wealth distribution are in fact outdated.

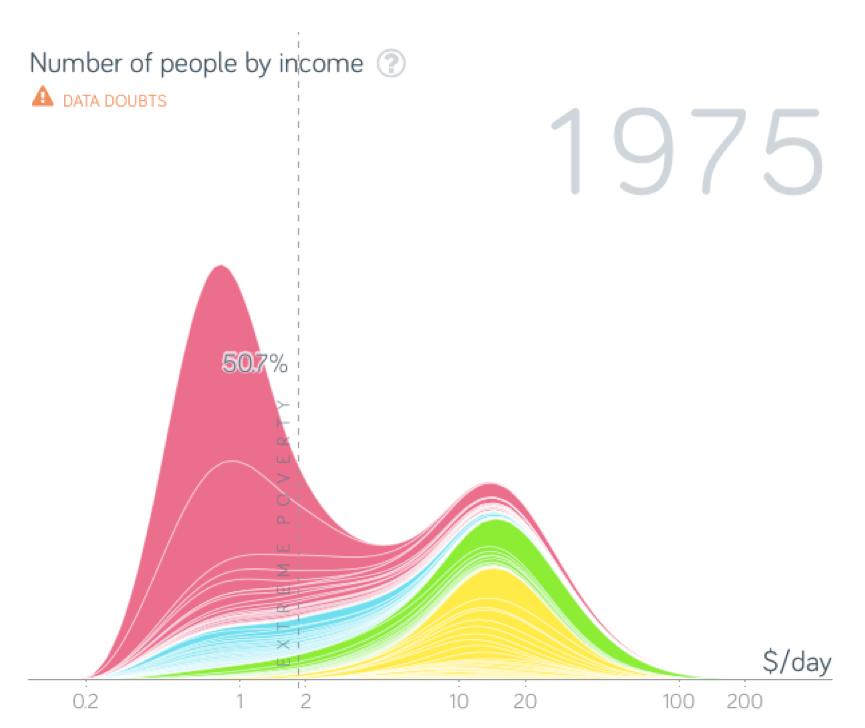

Figure 2: For comparison, the graph above represents the world in 1975. Over 50% of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty, and the vast majority of these were in Asia. There was a clear disparity between wealth in the traditional west and the rest.

The vast majority of the world are not only out of poverty, but earn almost the same amount of money as measured by US$/day, regardless of where they live. Understanding this is vital to interpreting our world and understanding healthcare challenges.

-

Let’s stop using the terms “Developing and Developed” to describe nations

In the same vein, on occasion, Professor Rosling mentioned that the terms developed and developing are not particularly useful in describing the world we live in today. Many of these terms are understandably established along political lines and regional categorizations. Nonetheless, their use is of minimal benefit.

We live in an incredibly rapidly changing world; the most peaceful two decades in recent history in terms of war with the highest global life expectancy. Globalisation, decolonization and the slight dismantling of national and geopolitical protectionist trends in recent decades have opened opportunities for previously suppressed and disadvantaged nations world over. It is my hope that what we are witnessing in this digital and globally connected era is the beginning of the democratization of trade, health and wealth.

-

Humans never lived in ecological balance with nature: they died in ecological balance with nature.

The world is getting better; not worse.

There has never been a better time for human life and civilization in known history as now. Today, globally, we live better than ever before**; longer than ever before; have fewer children whose chances of survival to reproductive age is the highest rate in recorded history.

If you didn’t know this, you’re not alone. Not only does fear mongering sell; but parents and teachers inform young people based on their experience of the world as it was when they were young, including ideas that their teachers and parents imparted to them.

-

Population growth is inevitable

Professor Rosling is arguably best known for his views, supported by statistical projections, on population growth.

The “population growth is the problem” argument has always been a personal pet peeve. But I’ll write more on this in future.

The global population will likely reach 11 billion before reaching a plateau. This is not because more people will be born; but rather that the additional 3.5 billion people are already alive.

Dr Rosling often demonstrated this in a very accessible way with the use of plastic or Styrofoam boxes. He referred to this concept as the global population ‘fill up’.

In short, today very few people die between infancy and the age of 65. Thus, as we are having only enough children to roughly replace ourselves, the population will not grow from new births: it will grow from later deaths. The global population fill-up of adults.

“We have reached the age of Peak Child” (2014)

-

The future will be dictated by love, not fear.

Child mortality is the primary driver of fertility rates. The number of babies per woman only decreases when the chances of child survival increase. When families are uncertain of the chances of survival of their children, they will have more children. Today, the global average number of babies per woman is 2.4. In Vietnam, the average number of babies per woman is 1.7. In Bangladesh, 2.14. In Yemen, 3.83 and 2.34 in South Africa.

Many make assumptions about fertility rates based on the world as it was in the 1970s. Rich countries had long life and small families whilst poor countries had shorter lives but larger family. This simply is not the world we live in: the world we live in is changing rapidly; and continues to do so.

Dr Rosling spoke on how most young couples today have access to some form of contraception; and with time and changing social norms; family values have started to shift towards an increased importance of how well one’s children are doing as opposed to how numerous they are. This is how love will dictate the composition of families, rather than fears based on child and infant mortalities.

-

We need to use useful metrics

A good example of a metric that is commonly used to discuss global disease profiles is the percentage of adults within a particular population living with HIV.

This is not a particularly useful metric. In a nation such as South Africa, Antiretroviral Treatment is free to any person or persons presenting themselves at a clinic or hospital. Moreover, whilst highly costly, budget provisions have been made for on-going counselling and lifetime maintenance of treatment and management of disease including co-infections. Thus, a large proportion of HIV positive individuals have been able to receive the treatment to live a long and healthy life. Indeed, provided that there are newly infected individuals, the number will continue to rise, and this is only a sign that those who contract HIV are surviving: not progressing to AIDS or succumbing to other infections.

This is an example of a middle-income country. Contracting HIV in a low-income country can be very different. Often, people who contract HIV in low-income, very low income or some land locked developing states, do not survive unless they have the personal funding to give them access to treatment. In some instances, free treatment is made available for periods of time but without the consistency vital to antiretroviral therapy. Such a nation may have a lower percentage of infected individuals due to survival rates. Thus, this metric is not particularly useful, nor encouraging.

I might suggest more useful metrics to communicate the same data in a stronger way. Perhaps “% HIV positive patients on ART for >2 years”; or “% HIV positive patients progressing to AIDS”

7. Healthcare spending is more important than GDP in dictating national public health outcomes

Wealth does not need to precede health (see: Vietnam; Cuba), but it sure does help. Strategic allocation of resources both between and within nations can act as a major driver of positive health outcomes even at a relatively low GDP, middle-income nations can create conditions to ensure long length of life.

The challenge faced by many of such nations that are winning the fight against communicable disease is the dual burden created by the fast emergence of a range of non-communicable diseases coexisting alongside traditional disease profiles. I have written about this in the past here.

These governments face the challenge of the incredible financial challenge of dealing with NCDs such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases, kidney failure and diseases of old age such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimers. Thus, time will tell if strategic efforts in prevention of these in many nations will yield useful results, or if, indeed, a third paradigm shift will occur in the management of NCDs in low and middle-income nations.